Amy Raphael delves into the science behind forest bathing to reveal why we should all be spending more time in the company of trees

The term shinrin-yoku – or “forest bathing” – originated in Japan in the 1980s, both as a quick fix for burnout and to encourage people to reconnect with nature. It’s not, however, as simple as wandering aimlessly; it’s rather about taking a moment to immerse yourself in the sights, sounds and smells of the forest. Since it’s all about being in the moment, there is, of course, an obvious link to mindfulness, but previous experience of meditation isn’t necessary. Simply put your phone away, allow your breathing to slow down and let the forest embrace you.

The physiological effects of shinrin-yoku have been well researched. Scientific studies show that trees release chemicals called phytoncides, which boost the immune system. Forest bathing can also lower both the pulse rate and concentrations of cortisol (the latter plays an important part in stress response, but too much can be dangerous). It can also lower stress, raise energy levels and improve concentration. It’s the perfect antidote to modern life and it costs nothing.

In his seminal 2018 book, Shinrin-Yoku: The Art and Science of Forest Bathing, Dr Qing Li wrote about the wonder of trees. For example, a group of researchers in Toronto discovered that having 10 more trees on a city block could make residents feel seven years younger. Eleven more trees could lower cardio-metabolic illness, diabetes and obesity. It’s hardly surprising, since trees clean the air by capturing and storing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. Scientists refer to this as the “biophilia effect” – by breathing in the scent of the trees and the forest floor, we can be restored.

Millions of tonnes of carbon are stored in UK forests, yet we have often undervalued trees. In 2022, wooded areas covered only 13 per cent of the UK – and ancient woodland a measly 2.5 per cent. Ancient woodland is home to more threatened species than any other, but up to 70 per cent of ancient woodlands in the UK have already been lost or damaged.

We must, therefore, embrace the woods that remain. Not, perhaps, by literally hugging a tree, but by spending time in the company of trees. Ancient woodland – forested areas that have persisted since 1600 and that are widely agreed to be irreplaceable – is often spectacular: see Wistman’s Wood on Dartmoor, Savernake Forest in Wiltshire, Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire, Burnham Beeches in Buckinghamshire and the most famous of them all, Sherwood Forest in Nottingham. There is even an ancient woodland in Muswell Hill, north London, called Coldfall Wood, that covers 14 hectares of the capital – as well as small pockets of trees right in the centre of the city, including the silver birch planted between Tate Modern and the Thames and the plane trees circling Tate Britain (the latter sheds their camo-bark to clear away pollution). Neither collection of trees could be classified as a forest, but as the Toronto research illustrated, every tree counts.

Interest in shinrin-yoku has exploded in this country in the past decade. So much so, in fact, that The Forest Bathing Institute (TFBI) was founded by Gary Evans and his wife Olga Terebenina, in Surrey in 2016, to offer therapeutic forest bathing experiences in various locations around the UK, including the New Forest and Newlands Corner near Guildford. Dame Judi Dench, who often discusses her love of trees, recently became a patron, which is a very particular kind of kitemark. TFBI points out that while walking in the forest alone is always a good thing, guided groups have more of an impact on the parasympathetic nervous system, which slows the heart rate down. Spending time in nature with other like-minded people encourages anxiety levels to drop.

It should come as no surprise that shinrin-yoku is prescribed by doctors in Japan – or that the NHS is beginning to roll out forest bathing sessions for certain groups of vulnerable people. At a time when the biodiversity crisis is making headlines, woodland offers ecotherapy, clean air, incredible scents and nature as it was meant to be experienced. Dr Qing Lin points out that while we tend to only use our eyes and ears indoors, we ‘open up our senses’ when we connect with the natural world. Perhaps WH Auden said it best when he wrote in Woods, one of his early 1950s poems from a sequence called Bucolics, ‘A culture is no better than its woods.’

Amy Raphael is an author and journalist who writes about popular culture and whose words have appeared in publications including The Face, Esquire, NME, Rolling Stone and The Guardian

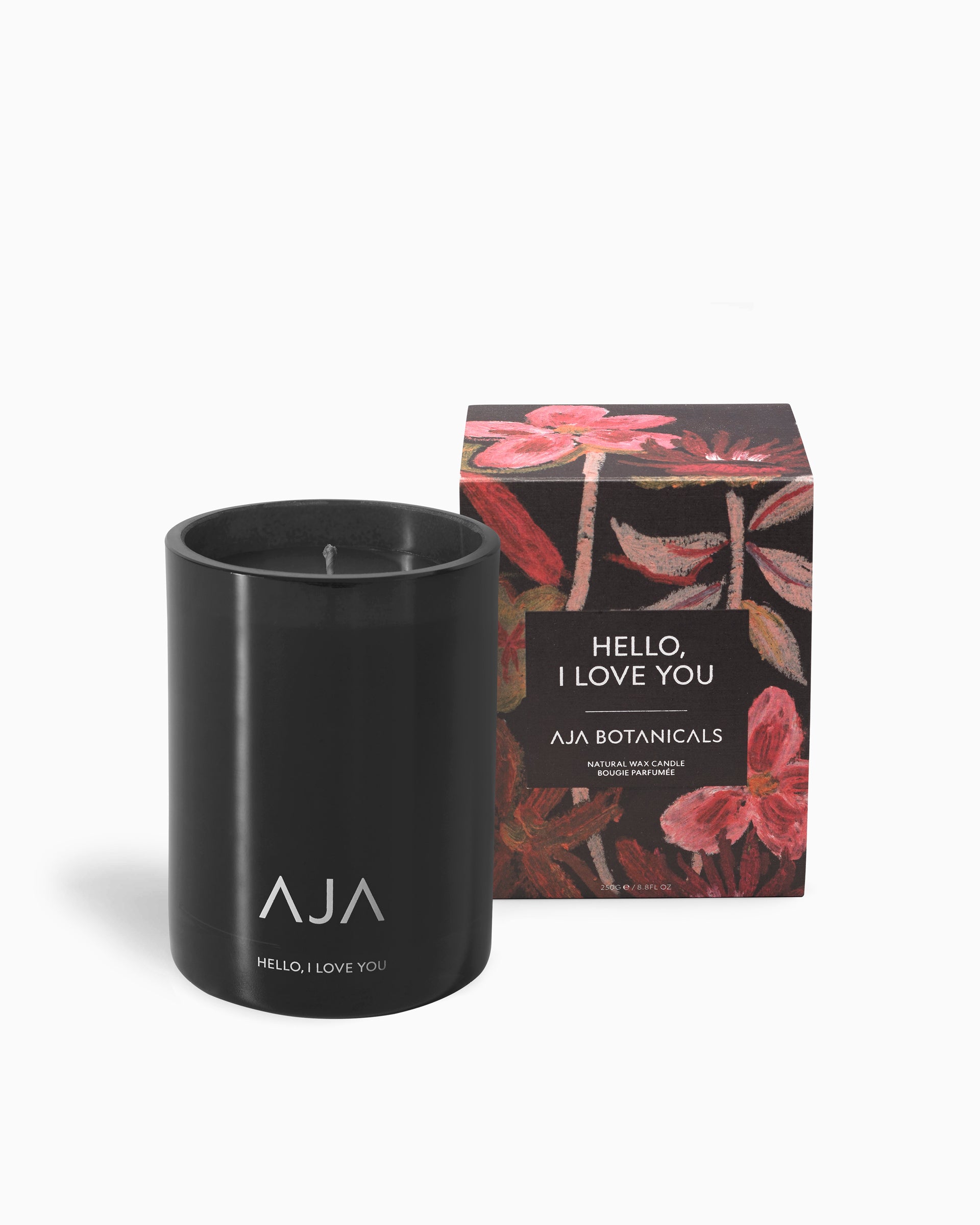

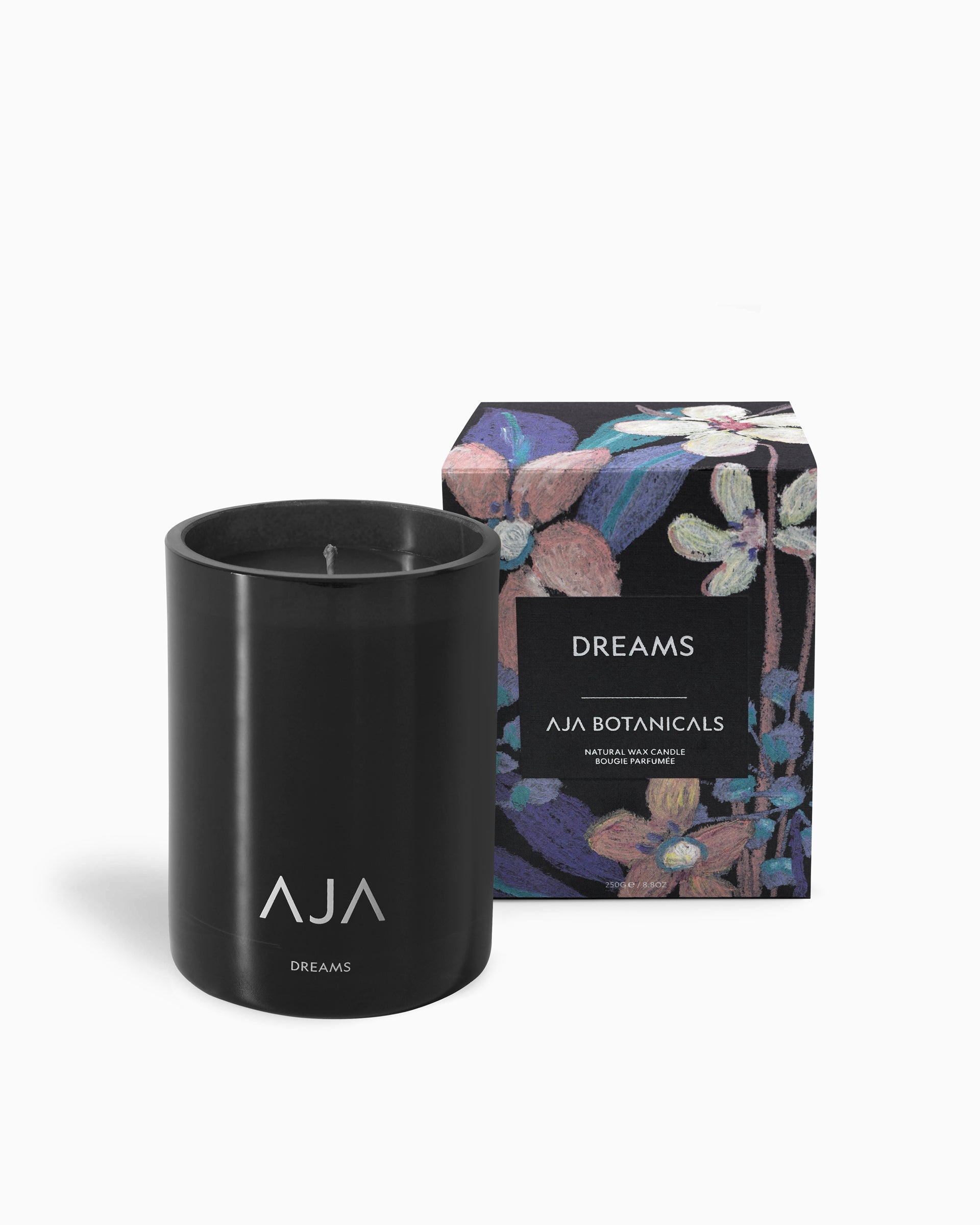

Inspired by the wonders of the forest, Aja Botanicals’ Into The Mystic fragrance brings a sense of nature and the scent of fresh woodland into your home. Discover the range here.

Photo by Lukasz Szmigiel on Unsplash